The important differences between Hazard, Danger, Risk and Fear when considering a Deep Geologic Repository for used nuclear fuel.

We are really pleased that the chronicle Journal ran this piece on April 15. In the nuclear industry we are used to managing hazards, dangers and risks and we are used to removing fear from the equation to ensure we focus on the reality. But in everyday life these issues are conflated ….

In everyday conversation we often mix up the words hazard, danger and risk. But they are not the same and using them incorrectly gives rise to unnecessary fears.

Hazard describes something that could, in theory, cause harm. Danger arises when there is a mechanism for the hazard to cause harm. Risk combines the likelihood that any danger could cause harm with the significance of the harm it might cause.

Fear is an emotional response to the perception of the risk, and it may or may not be rational.

The popular explanation of the differences is based around sharks. There is no doubt that sharks are a hazard, but they are not a danger unless you are swimming in an ocean. It is not risky to swim in the ocean if you are not where large sharks are found; it is risky if it’s feeding time in an area where Great Whites are active. You have a right to be genuinely fearful if your boat is capsizing off the Florida coast, but nightmares experienced after seeing Jaws cause fear that is unnecessary.

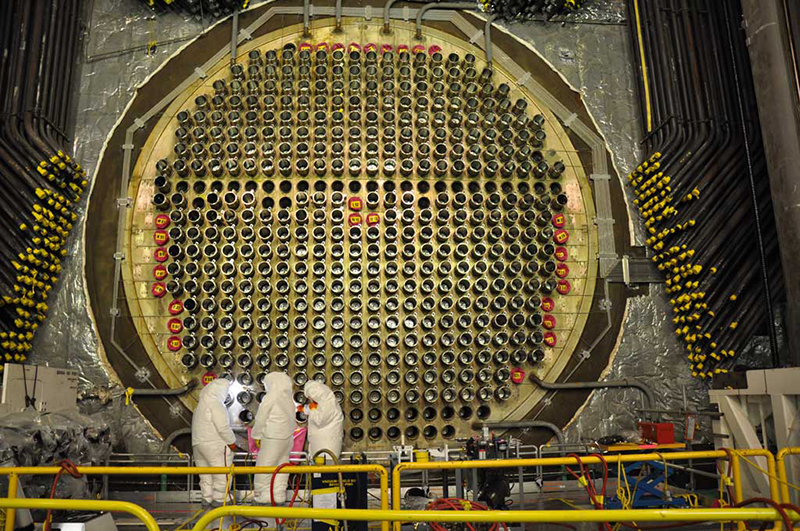

Like sharks there can be no doubt that used nuclear fuel is hazardous. In fact, there are two very significant hazards. The first is that it emits quantities of radiation that would be fatal if someone was exposed to it and the second is that it contains a radiotoxic material. The first could nail somone if they simply stood near an exposed fuel bundle, the second would make someone very sick if they ingested any of it.

But used nuclear fuel will not be dangerous while in a Deep Geologic Repository as there is no mechanism whereby either hazard can do harm. Only a few metres of rock is enough to completely shield the radiation and there are hundreds of meters of rock between life and the used fuel. And as there are no people around half a kilometer underground there is no one that could eat or sniff it even if it were not in impenetrable containers, which it is.

Despite this many people consider repositories to be a considerable risk and are very fearful about them even though they cannot put their finger on what the risk might be or why they are fearing it.

It appears that some people imagine that the bundles or pellets of used fuel might reappear at the surface after some unpredictable Sharknado-like event. It’s hard to conceive of how this could happen but, as many people that are against the repository will say, it’s also impossible to prove that it’s impossible. Proving negatives is typically impossible.

Regardless even if a fuel bundle did come to the surface it’s still not a problem if mankind is around as it could just be contained and shielded so that there is once again a hazard but no danger. Even if there was a possibility that it could happen it would have no consequences and so is not a big risk and should not be feared.

Other people appear to imagine that the repository might “leak” and concentrated radioactive material would flow out of the repository and then upwards to the surface. This is impossible. Used fuel is an unreactive, largely insoluble, solid and there are no gaps in the rock through which a liquid could “flow”. So, fears of a leak, in any normal use of the word, are groundless.

That is not to say that some radiotoxic materials may not escape from the repository. Some of the decay products (elements that result from the radioactive decay of the material in the used fuel) are more mobile and could diffuse out of the repository and if there were a transport mechanism t could migrate towards the surface.

The likelihood of this happening is hard to establish. It requires the breakdown of multiple engineered barriers that are designed and tested to last forever, and the assumption of a flow of water that does not presently exist. But if it were possible, it would probably take hundreds of thousands of years, ample time to manage it. This risk is being studied in considerable detail.

Risk is the combination of likelihood and consequence, and it should be obvious that we are now talking about a consequence that, even in the worst case, will not make much difference to anything. After the slow migration into such a large area, it will become very dilute, and so would likely not make much difference.

So basically, a DGR is a hazard, but it poses no danger and very little risk even to the long-term future. The risk is vanishingly small because the serious events people imagine are not possible and the possible (though unlikely) consequences would take a very long time, would be manageable and even after that would be insignificant.

And yet people remain fearful.

Many of these fears arise from scaremongering in which hazard is deliberately conflated with danger, and risk is misrepresented to create fear.

But looked at in the cold light of day an important truth is revealed and that is that a DGR is not a desperate last measure as it is often portrayed but is a world-leading approach to global sustainability, in which a man-made hazard is dealt with in a way that creates no danger.

The Canadian Nuclear Society

Popular Core Business Articles

- The important differences between Hazard, Danger, Risk and Fear when considering a Deep Geologic Repository for used nuclear fuel.

- Deep Geologic Repositories (DGRs)? Distressed purchase or Jewel in the Nuclear Crown

- An article by the Breakthrough Institute

- How do we quickly and succinctly explain why wind and solar are not cheap?

- The Titanic Fallacy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.